Drivers of continued implementation of cultural competence in substance use disorder treatment

Highlights

•Continued implementation of culturally responsive practices was uneven in the system studied. •Director's leadership predicted implementation of all five practices •Latino directors with high leadership predicted implementation of three of the five practices.

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine whether the key characteristics of organizational decision makers predicted continued implementation of five different practices that represent organizational cultural competence in one of the largest and most diverse substance use disorder (SUD) treatment systems in the United States. We analyzed data collected from SUD treatment programs at four-time points: 2011 (N = 115), 2013 (N = 111), 2015 (N = 106), and 2017 (N = 94). We conducted five mixed-effect linear regression models, one per each outcome to examine the extent to which program director's transformational leadership and ethnic background (Latino) predicted (1) knowledge of minority community needs; (2) development of resources and linkages to serve minorities; (3) reaching out to minority communities; (4) hiring and retention of staff members from minority backgrounds; and (5) development of policies and procedures to effectively respond to the service needs of minority patients. Results show that two of the five practices continued implementation at same degree (resources and linkages and policies and procedures), one practice increased degree of implementation (knowledge), while two practices reduced degree of implementation (staffing and outreach to communities) over the six-year period. Directorial leadership was positively associated with the continued implementation of all five practices. Latino directors were associated with an increase in knowledge of minority communities, but a decrease in resources and linkages and policies and procedures to serve minorities. On the other hand, interactions showed that leadership among Latino directors increased staffing over time and led to increases in resources and linkages and policies and procedures overtime. Overall, continued implementation of culturally responsive practices was uneven in the SUD treatment system studied. But program directors' transformational leadership and ethnic background played a critical role in increasing the implementation of key practices over time. Findings have implications for developing and testing culturally grounded leadership interventions for program directors to ensure the continued and increased implementation of practices that are necessary to improve standards of care in minority health.

1. Introduction

Health care organizations in the United States are increasingly called upon to improve quality of care by delivering services that respond to the cultural and linguistic service needs of an increasingly diverse population. One way to accomplish this is through developing organizational cultural competence, generally defined as a set of behaviors, attitudes, and policies that allow an organization to work effectively in cross-cultural situations (Cross, Bazron, Dennis, & Isaacs, 1989). Cultural competence has become widely accepted in health care systems as a way of improving the quality of care (Betancourt, Green, Carrillo, & Park, 2005; Brach & Fraser, 2000; Shelton, Cooper, & Stirman, 2018). Organizations that are responsive to culturally competent practices, i.e., the ability to consider the cultural and linguistic characteristics of clients in the structure and delivery of health care (Betancourt et al., 2005; Brach & Fraser, 2000) have a greater likelihood of improving outcomes and decreasing racial/ethnic disparities in health care (Institute of Medicine, 2001, Institute of Medicine, 2013; Shelton et al., 2018). While culturally competent practices have become more commonly delivered in health care organizations (Weech-Maldonado, Al-Amin, Nishimi, & Salam, 2011), there is still limited understanding of the drivers of long-term implementation. Implementation refers to the routine and on-going use of organizational practices or delivery of services (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014). Because many research studies measure implementation with cross-sectional designs, it is critical to pursue implementation using repeated measures that show on-going use of policy, organizational, and service delivery practices that are considered culturally competent (Aarons, Wells, Zagursky, Fettes, & Palinkas, 2009; Fixsen, Naoom, Blasé, Friedman, & Wallace, 2005; Guerrero, 2013; Guerrero & Kim, 2013; Howard, 2003). Providers' commitment to respond to the cultural and linguistic service needs of their patient populations seem to play a critical role in maintaining culturally responsive practices (Brach & Fraser, 2000; Cross et al., 1989; Guerrero, 2012; Harper et al., 2009; Weech-Maldonado et al., 2011). Overtime, this commitment is expected to improve quality of care, affecting outcomes such as higher engagement in care (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2014). The study of continued implementation should be distinguished from the study of sustaining practices. Unlike implementation research, examination of sustainment starts with the assumption that the organization(s) had fully implemented the target practices at baseline. This is not the case in most research studies that observe treatment as usual and or examine a set of different organizations at the same stage of implementation of one or several practices. The implementation process faces its own set of barriers and facilitators (Beune, Haafkens, & Bindels, 2011; Grol & Wensing, 2004; Williams, 2011). These have been given little attention in examining the continuation of implementation efforts of practices such as cultural competence (Aarons, Horowitz, Dlugosz, & Ehrhart, 2012; Aarons, Hurlburt, & Horwitz, 2011; Bond, Drake, Becker, & Noel, 2016; Delphin-Rittmon, Andres-Hyman, Flanagan, & Davidson, 2012; Guerrero, Marsh, Khachikian, Amaro, & Vega, 2013; Wiltsey Stirman et al., 2012). The only prior study using a longitudinal approach to steady delivery of cultural competence focused on organizational and system level practices in hospitals (Delphin-Rittmon et al., 2012). These authors highlight drivers of long-term or continued implementation that include managerial-level support and responsibility, maintaining a positive patient and provider partnership, conducting assessments of culturally competent services, ensuring linguistic competence, maintaining a culturally competent workforce, and focusing efforts on advancing action plans. Generally, health care organization truly committed to the delivery of culturally responsive services is the ones continuing implementation efforts of such services (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014). Yet, there are limited theoretical frameworks that have informed the organizational factors that play a role in continuing the implementation of culturally competent practices in health care services long term.

1.1. Framework

There are several frameworks on implementation of organizational and service practices. But very few of those frameworks address the issue of variation in the implementation process or the on-going enacting or delivery of practices or services overtime. One of the most concrete frameworks that pay careful attention to the implementation process is the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation and Sustainment (EPIS) framework (Aarons et al., 2011). Unlike other frameworks, the EPIS framework makes a distinction between implementation and sustainment. It posits that once practices are delivered with fidelity as a routine, the process of sustainment begins. Emerging studies in SUD treatment have assessed implementation at baseline, and then examine factors that promoted sustainment overtime (Hunter et al., 2015, Hunter et al., 2017). Long-term implementation highlights the struggle of treatment programs to continue delivering practices overtime. Hence, a long-term implementation framework requires exploration with longitudinal data and a model that highlights factors that continuously promote delivery of practices, even when practices are not evenly delivered. The EPIS framework highlights outer and inner organizational factors, processes, and characteristics that lead organizations to implement practices steadily to sustain them. (Aarons et al., 2016; Damschroder et al., 2009; Meyers, Durlak, & Wandersman, 2012; Scheirer & Dearing, 2011; Stirman et al., 2012; Swain, Whitley, McHugo, & Drake, 2010). The outer context factors represent the environment that impacts the operations within the service systems. These factors include funding, policy, partnerships with providers, as well as academic-communities and system-level networks (Aarons et al., 2016). Public funding and regulation are particularly important, as they are well known to be key factors to continue delivering behavioral health practices in publicly funded settings (Aarons et al., 2016; Hedeker & Gibbons, 2006; Hunter et al., 2015, Hunter et al., 2017). Inner context factors refer to characteristics of the organizations, including those tasked with delivering the evidence-based interventions (Aarons et al., 2016). Some of the important inner factors are supervision and leadership, as well as workforce features, such as training and retention (Bond et al., 2014; Skolarus & Sales, 2014). Of importance for the long-term implementation of organizational and service delivery practices is leadership. Managers who enact consistent and effective leadership traits, such as communicating a clear vision for implementation and supporting the professional development of staff may better prepare their programs for continued implementation of cultural competence. Significant research suggests that transformational leadership is the leadership type that is associated with staff implementation efforts (Aarons, Ehrhart, Farahnak, & Sklar, 2014). Transformational leadership is defined as efforts to promote and facilitate organizational reform. These types of leaders achieve their objectives by raising followers' consciousness beyond personal interests, such that their interests are more aligned with organizational goals and vision (Edwards, Knight, Broome, & Flynn, 2010). The cultural background of individuals with decision making power and leadership potential has also become an important factor to consider in the study of long-term implementation of culturally responsive practices (Guerrero, 2013). Ethnic minority managers' ethnic background may enhance their commitment to cultural practices that represent their values and experiences serving racial/ethnic minorities. This familiarity may be a powerful enabler of implementation of culturally responsive practices. There is a need to address implementation in this context, as it can help SUD treatment programs located in minority communities to consistently respond to the cultural and language service needs of racial and ethnic minority patients (Delphin-Rittmon et al., 2012). We examined the relationship between director's transformational leadership and ethnic background and the continued implementation of five of the six culturally responsive practices accounting for key drivers of implementation. The responsive practices studied were: (1) knowledge of racial and ethnic minority community needs; (2) development of resources and linkages to serve racial and ethnic minorities; (3) reaching out to racial and ethnic minority communities; (4) hiring and retention of staff members from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds; and (5) development of policies and procedures to effectively respond to the service needs of racial and ethnic minority patients. The sixth practice (personal involvement in racial and ethnic minority communities) was not included in all years and therefore not included in the analysis. Implementation of cultural competence has become a priority in health care, partly because of the increased regulation from public funding (Brach & Fraser, 2000; Institute of Medicine, 2001, Institute of Medicine, 2013) and the need to eliminate health care disparities (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2014; Delphin-Rittmon et al., 2012; Weech-Maldonado et al., 2011). Therefore, we expected that within the past decade, delivery of culturally responsive practices would be continued over time. We also expected that program leadership would promote the continued implementation of culturally responsive practices. More specifically, we hypothesized that directors' transformational leadership would support the continued implementation by use of inspiration and motivation to encourage staff to continue enacting the desired practices (Aarons, Ehrhart, Farahnak, & Hurlburt, 2015; Edwards et al., 2010). In particular, ethnic minority [Latino] directors, who are more likely to have increased familiarity with culturally responsive practices and that have decision-making power may have more commitment to sustaining culturally responsive practices compared to non-upper managers and non-ethnic minority Whites (Guerrero, 2013; Guerrero & Kim, 2013). Guided by the EPIS framework, we posit that: Hypothesis 1 All five culturally competent practices (knowledge, resources and linkage, staffing, policies and procedures and outreach to communities) will be continually implemented from 2011 (Time 1) to 2017 (Time 4) among SUD treatment programs. Hypothesis 2 Director's transformational leadership will be positively associated with continued implementation of each of the five culturally competent practice among SUD treatment programs. Hypothesis 3 Latino directors, compared to non-Latino directors, will be associated with continued implementation of each of the five culturally competent practices in SUD treatment programs.

2. Methods

2.1. Sampling frame and data collection We used survey data from the “Integrated substance abuse treatment to eliminate disparities study” (Guerrero, 2013; Guerrero & Kim, 2013). These data were collected at four-time points (2011, 2013, 2015 and 2017). The program data included all SUD treatment programs located in communities of Los Angeles County with populations of 40% or more residents of Latino or African American background. Description of these data can be found elsewhere (Guerrero et al., 2015). Table 1 provides additional details. Table 1. Cultural Competence (Mean, standard deviation in parenthesis) and Manager Characteristics (Count, percentages in parenthesis). 2011 (N = 115) 2013 (N = 111) 2015 (N = 106) 2017 (N = 94) Cultural competence Knowledge*** 29.1 (4.8) 29.7 (3.8) 32.9 (3.8) 31.7 (4.8) Resources and linkages 27.4 (5.7) 27.6 (6.0) 27.2 (5.8) 27.0 (5.2) Staffing 26.5 (5.7) 27.0 (4.9) 25.9 (5.0) 26.3 (4.8) Policies and procedures 23.7 (6.6) 24.2 (5.8) 25.1 (6.0) 23.7 (5.7) Outreach*** 27.2 (6.7) 28.1 (5.2) 23.9 (5.9) 23.0 (6.1) Manager characteristics Male 37 (39.4%) 42 (40.0%) 36 (36.4%) 30 (33.3%) Latino 33 (34.7%) 41 (39.0%) 46 (46.5%) 41 (46.1%) Transformational leadership 39.0 (6.9) 39.5 (5.0) 38.7 (6.2) 37.8 (6.0) TJC accreditation 19 (17.0%) 25 (24.8%) 24 (24.2%) 26 (29.5%) Medicaid*** 81 (71.7%) 64 (62.1%) 82 (82.8%) 81 (92.0%) Years of experience in SUD treatment 12.9 (9.5) 10.4 (6.1) 10.9 (5.1) 11.0 (4.8) Percentage of graduate staff 17.1 (24.1) 19.9 (24.1) 25.2 (22.8) 21.1 (21.9) TJC: The Joint Commission. SUD: Substance use disorder. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. For this study, the unit of analyses is a publicly funded SUD treatment program defined as a program where outpatient SUD treatment comprises at least 75% of its services. The program data for the proposed project were composed of an average of three staff members per program, two counselors and one manager (director or supervisor), who have knowledge and understanding of policies, practices and services. These staffs were randomly selected from a list of total staff per program. To capture community-based care in racial and ethnic minority communities, the solo practitioners and programs located in criminal justice facilities were excluded. From a sampling frame of 282 programs that met the above criteria, at baseline (2011), we randomly select 147 SUD treatment programs in LA County. That baseline sample was used for the subsequent years (2013, 2015 and 2017). The data for the study were collected from program managers and staff via online surveys and during site-visits. The program response rates for online surveys at the site level were 92% in 2011, 91% in 2013, 90% in 2015, and 92% in 2017. Approximately 65% of programs allowed us to complete a site-visit to validate survey responses regarding program structure and services. We completed a check list relying on qualitative interviews with a subsample of supervisors, a review of printed material available at each provider site (e.g., brochures, group activities, posted signs). We crossed-check consistency of supervisor reports on survey measures. These data allowed us to confirm programs reporting the use of culturally and linguistically appropriate services and practices. The final analytic sample included 115 programs in 2011 (Time 1), 111 programs in 2013 (Time 2), 106 programs in 2015 (Time 3), and 94 programs in 2017. An average of 34 programs closed in each of the waves resulting in 38 programs included in all four years. Limited sources of funding and other barriers to service delivery, which plague these programs, may explain the increased risk of closure that we observed. Programs not included in subsequent years did not vary on the variables of interest from those in the analytic sample (P > 0.05).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Dependent variables

Our cultural competence measure is represented by five organizational practices (Mason, 1995), supported by the extant literature (Brach & Fraser, 2000; Cross et al., 1989; Harper et al., 2009). This measure has 57 items, and for each item, we measured supervisors' report on (1) their program staff's knowledge of racial and ethnic minority community needs (e.g., Do you know the prevailing beliefs, customs, norms and values of Latinos in your service area?) (12 items); (2) development of resources and linkages to serve racial and ethnic minorities (e.g., Does your agency utilize interpreters to work with limited English-proficient Latinos?) (11 items); (3) reaching out to racial and ethnic minority communities (e.g., Does your program participate in community events?) (9 items); (4) hiring and retention of staff members from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds (e.g., Are there Latinos represented in managerial and administrative positions?) (13 items); and (5) development of policies and procedures to effectively respond to the service needs of racial and ethnic minority patients (e.g., Does your agency translate agency materials into Spanish?) (12 items). As previously mentioned, the practice of personal involvement in racial and ethnic minority communities was not included because the measure items were not present in all years. Staff rated items were on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = not at all to 4 = often). Cronbach's α coefficients on these items ranged from 0.72 to 0.98. This measure of cultural sensitivity and responsiveness has been used in other studies (Guerrero, 2013; Guerrero & Kim, 2013).

2.2.2. Independent variables

Our main independent variables were transformational leadership and Latino ethnic group among program managers. Transformational leadership was measured using the abbreviated version (Broome, Knight, Edwards, & Flynn, 2009) of the Survey of Transformational Leadership developed for SUD treatment (Edwards et al., 2010). Supervisors and counselors responded to the seven items representing Director's transformational leadership qualities on a five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Items included questions such as “leads by example,” “inspires others with his/her plans for this facility for the future,” and “takes time to listen carefully to and discuss people's concerns.” cores were averaged by program with higher scores representing employee perception of greater transformational leadership by the director of their program (Edwards et al., 2010). This measure has been used in several studies in SUD treatment (e.g., Guerrero et al., 2015; Guerrero et al., 2016; Guerrero, Fenwick, & Kong, 2017). The Cronbach's alpha for the transformational leadership measure in this study was 0.92. Program participants self-reported whether they identified with Latino as their ethnic group. We relied on this indicator to describe Latino versus non-Latino managers.

2.2.3. Control variables

Our control variables included regulation, professionalization, and work experience as key factors associated with delivery of cultural competence in other studies. To measure regulation, we asked whether the program had a regulatory accreditation by The Joint Commission. The professionalization measure is the percentage of employees in the organization with a graduate degree. Work experience was measured as average years of experience in the SUD treatment field. Years of SUD treatment experience was averaged among staff to represent each program. Finally, we asked managers whether the program accepts Medicaid. These factors have been accounted for in prior SUD treatment studies regarding implementation (D'Aunno, 2006; Guerrero, 2010).

2.3. Analytic strategy

Considering program as the unit of analysis, we relied on multilevel linear regressions to account for programs nested in data collection waves by assigning a random intercept to each program in a wave/year to examine direct and moderated relationships (Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992). Our data is not panel with repeated measures meaning not all programs participated in all four separate years. The specific analytical procedure was mixed-effect linear regression models run in STATA version 12. Mixed effects models are the most appropriate for our data because they allow for correlation between group-varying betas, multiple levels of nested groups (staff/programs/year), analysis of incomplete data across years, and testing systematic differences in the population mean quadratic curve when comparing conditions (e.g., Latino vs. non-Latino Director) (Hedeker & Gibbons, 2006). Random intercepts were assigned for each program in each year, while the fixed effects were assumed for all the other variables. We also relied on mixed effects models to test moderated relationships or interactions between manager ethnic group (Latino vs. non-Latino) and leadership, and between Latino and year, relative to the outcome measure.

3. Results

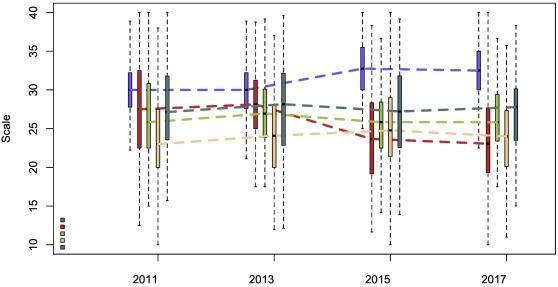

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for cultural competence, and manager characteristics, at four time points (years 2011, 2013, 2015, 2017), respectively. Staff knowledge of racial and ethnic minority community needs, as well as reaching out to racial and ethnic minority communities were found to be statistically significant. A program accepting Medicaid was also significant. Fig. 1 shows that the only practice that significantly increased from 2011 to 2017 was knowledge of ethnically diverse communities. In contrast, outreach to these communities significantly decreased over the course of the four time points.

We found partial support for Hypothesis 1 which posited that all five culturally competent practices (knowledge, resources and linkage, staffing, policies and procedures and outreach to communities) will be continually implemented from 2011 (Time 1) to 2017 (Time 4) among SUD treatment programs. Findings show that two practices (policies and procedures (b = −0.358; SE = 0.312 and resources and linkages (b = −0.566; SE = 0.302)) continued at their same level of implementation across years given their non-statistical significant change. One practice, knowledge was continually implemented across years (b = 1.124; SE = 0.213), while two culturally competent practices decreased implementation across years (staffing (b = −0.722; SE = 0.324), and outreach to communities (b = −1.641; SE = 0.246). Results from the mixed-effect linear regression models are shown in Table 2. Table 2. Five random-intercept linear regression models on implementation of culturally competent practices.

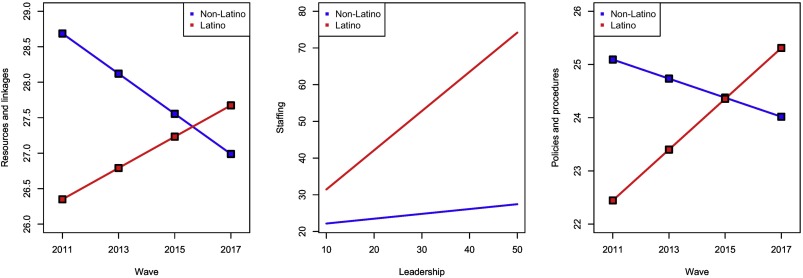

Knowledge Outreach to communities Staffing Org policies & procedures Resources and linkage Beta SE p value Beta SE p value Beta SE p value Beta SE p value Beta SE p value Manager characteristics Male −0.156 0.454 0.732 −0.677 0.615 0.271 −0.241 0.562 0.668 1.205 0.600 0.045 0.077 0.585 0.896 Latino 1.397 0.453 0.002 0.467 0.636 0.463 −0.080 0.978 0.935 −2.647 1.012 0.009 −2.337 0.991 0.018 Leadership 0.130 0.036 0.000 0.200 0.047 0.000 0.132 0.044 0.003 0.232 0.046 0.000 0.178 0.045 0.000 TJC −0.118 0.521 0.821 0.550 0.706 0.436 −0.214 0.641 0.739 −0.157 0.684 0.819 0.423 0.666 0.526 Medicaid −0.081 0.537 0.879 −0.599 0.778 0.441 0.925 0.693 0.182 0.492 0.770 0.523 0.150 0.734 0.839 Years in SUD treatment 0.051 0.034 0.127 0.053 0.047 0.262 0.087 0.043 0.043 0.085 0.048 0.078 0.051 0.047 0.279 Percentage of graduate staff −0.002 0.010 0.828 0.009 0.014 0.538 −0.001 0.013 0.963 0.012 0.014 0.392 0.008 0.014 0.583 Yeara 1.124 0.213 0.000 −1.641 0.246 0.000 −0.722 0.324 0.026 −0.358 0.312 0.252 −0.566 0.302 0.061 Interactions Latino*leadership 0.937 0.484 0.053 Latino*Year 1.313 0.479 0.006 1.007 0.469 0.032 TJC: The Joint Commission, SUD: Substance use disorder a2011 is the reference year Hypothesis 2 was supported. Transformational program leadership was positively associated with continued implementation of each of the culturally competent practice among SUD treatment programs. These practices included knowledge (b = 0.130; SE = 0.036), resources and linkage (b = 0.178; SE = 0.045), staffing (b = 0.132; SE = 0.044), policies and procedures (b = 0.232; SE = 0.046), and outreach to communities (b = 0.200; SE = 0.047). Hypothesis 3 was partially supported. Programs with Latino directors, compared to those with non-Latino, were associated with continued implementation of one practice, and decreased implementation of two practices. Programs with Latino directors were associated with higher implementation of knowledge (b = 1.397; SE = 0.453), but also associated with lower implementation of resources and linkage (b = −2.337; SE = 0.991), and policies and procedures (b = −2.647; SE = 1.012). However, when considering the interaction between Latino director and year, resources and linkage (b = 1.007; SE = 0.469) and policies and procedures (b = 1.313; SE = 0.497) were associated with increased implementation compared to non-Latino director and baseline year. This means that implementation of resources and linkages and policies and procedures continued across years in programs with Latino directors versus non-Latino directors (Fig. 2).

There was also a significant interaction between Latino director and leadership and diverse staffing (b = 0.937; SE = 0.484). In other words, compared to non-Latino directors, programs with Latino directors and high leadership were associated with higher implementation of diverse staffing. Director's gender (male) was associated with increased implementation of policies and procedures (b = 1.205; SE = 0.600). The average number of years of experience in SAT among program was associated with increased implementation of staffing (b = 0.087; SE = 0.043).

4. Discussion

This study examined whether five different practices that represent organizational cultural competence were continually implemented in one of the largest and most diverse substance use disorder (SUD) treatment systems in the United States. To explain continued implementation, we examined the role of program directors' ethnic background (Latino) and transformational leadership. Findings show that two of the five practices were continually implemented (i.e., resources and linkages and policies and procedures), one practice increased in implementation degree (i.e., knowledge), while two practices decreased (i.e., staffing and outreach to communities). These findings provide initial evidence of the variation in implementation of culturally competent practices in community-based SUD treatment in Los Angeles County, California from 2011 to 2017. Transformational leadership among program directors was a robust driver of implementation across all culturally responsive practices. Also, programs with Latino directors were associated with higher knowledge of ethnic minority communities than programs with non-Latino directors. However, these programs with Latino directors implemented fewer resources and linkages in minority communities and established fewer policies and procedures that were culturally responsive compared with programs with non-Latino directors. But when examined overtime, programs with Latino directors increased the implementation of these two practices. Albeit conjectural, the difference between decrease and increased implementation of these two practices may rely more on Latino directors' experience and tenure in the program as suggested by the significant interaction between Latino director and Year. This finding is consistent with national studies focusing on the role of the ethnic minority leader and experience in diversifying the workforce in SUD treatment (Guerrero, 2013). The EPIS framework emphasizes the role of leadership to support implementation efforts (Aarons et al., 2014, Aarons et al., 2015, Aarons et al., 2016). Findings from this study show that program directors' transformational leadership was associated with increased implementation of the five culturally responsive practices. Leadership capacity, particularly among Latino directors plays an important role in investing in culturally responsive practices (Guerrero et al., 2015). Overall, understanding why and how Latino managers prioritize delivering quality of care for racial and ethnic minority clients is the next step in this line of research. This is one of the first studies to establish a baseline understanding of implementation of cultural competence across different time points in community-based outpatient SUD treatment. Years (2011, 2013, 2015 and 2017), which we use as a measure of time, was associated with an increase in knowledge of minority communities and a decrease in outreach to ethnic minority communities and diverse staffing. Albeit conjectural, this finding may suggest that as program staff know more about minority communities, they may feel less inclined to reach out to these communities. This finding has important implications for preparing the workforce for delivering culturally responsive health care services to minority communities (Guerrero et al., 2013). For instance, to enhance access to care, it is critical to train the treatment workforce to interact with and directly learn from minority communities. Program leaders and staff can use this interaction to educate community members on SUDs and the benefits of treatment and recovery to promote health in their communities. Finally, we found no relationship between programs Medicaid payment acceptance and TJC certification and the continued implementation of culturally competence practices. Medicaid and TJC expect programs to provide services within a cultural competence framework (Brach & Fraser, 2000), and a prior study found a cross-sectional relationship between Medicaid and culturally competent policies and procedures (Guerrero & Kim, 2013). Yet, this null finding suggests a limited program response to institutional pressures to continue delivering cultural competence.

4.1. Limitations

We would like to recognize limitations of the study. First, survey measures of cultural competence are likely to over-report prevalence. However, this issue was mitigated by corroboration of respondent reports in the qualitative data obtained during site visits conducted in all four time points. Second, our data is not panel with repeated program measures. Program closure prevented the inclusion of enough programs across years to analyze. Over 30% of programs closed at each wave resulting in only 38 programs participating across waves. However, our analytical approach (mixed-effect regression models) are adequate to model these unbalanced data and provide robust estimates. Another limitation is that 6 years may be a restricted period to determine full implementation. But in health and human services, change of practice is constant. In addition, an indicator of implementation of practices, measured by services that are not billable, show promise for these organizations' commitment to quality of service delivery, especially for individuals from racial and ethnic minority groups. Finally, findings can only generalize to publicly funded SUD treatment programs serving communities with a Latino population of 40% or more, but this corresponds to 7.7 million residents in L.A. County.

4.2. Conclusion

The present study contributes new findings indicating that most of the culturally competent practices were stable over the six-year period. The sample of programs located in racial/ethnic diverse communities in a large SUD treatment implemented culturally responsive policies (e.g., translate agency materials into Spanish), practices (e.g., utilize interpreters to work with limited English-proficient Latinos) and resources (e.g., use cultural brokers to enhance outcomes) these practices overall but with some variation. Programs appear to be investing in providing services to minority communities despite a political climate that may not promote quality of care for racial and ethnic minority and immigrant communities. The significance of director's transformational leadership behaviors in continuing the implementation of these practices was further identified as a central element, yet again, with ethnic minority leaders predicting implementation more so than their non-Latino counterparts. This is consistent with other studies of implementation of culturally responsive practices (Guerrero, 2013; Guerrero et al., 2017). These findings can guide efforts based on the importance of leadership and leaders of ethnic minority backgrounds as proponents of cultural competence implementation. For example, programs that included Latino directors increased knowledge of ethnic minority communities. This brings to light the importance of increasing culturally responsive practices in SUD treatment organizations. Advancing and sustaining leadership that promotes cultural competence through culturally responsive policies, practices, and resources is an important next step to build a system of quality of care. Promoting a culturally and linguistically diverse program for healthcare organizations will provide a more responsive way of addressing the needs of the service area and client population. It is critical to further provide more evidence of key organizational factors driving implementation of culturally responsive care, and with these efforts increase quality of care and eliminate disparities. Acknowledgements Support for this research and manuscript preparation was provided by a National Institute of Drug Abuse research grant (R33DA035634-03, PI: Erick Guerrero) and an implementation fellowship training grant (R25 MH080916, PI: Enola Proctor). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank treatment providers for their participation in this study and appreciate Dr. Gary Tsai and Dr. Tina Kim from the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, Substance Abuse Prevention and Control for their support. Conflict of interests, ethics approval, and consent to participate The manuscript authors declare that they have no conflict of interests, financial or otherwise, and that they consent to publish this manuscript. Content presented in this manuscript has not been published elsewhere. This research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board at University of Southern California (No. UP-14-00395). Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from participants.

One thought on “Drivers of continued implementation of cultural competence in substance use disorder treatment”

Comments are closed.